Making change happen

We live in what has been termed VUCA times: volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. Certainly the past few years have seen the world turned upside down by a pandemic and now by a war that threatens peace in Europe. But given it was the Greek philosopher Heraclitus who said, ‘the only constant in life is change’, I rather suspect the pace and scale of change has always felt overwhelming.

As a leader knowing how to navigate and respond to change is therefore an essential skill, and one which is often part of the leadership courses I design and run for organisations. As a leadership and organisational coach enabling others to create and respond to change is my core business, so I thought it might be useful to share some of the tools I regularly use to help others understand, respond to and plan for change.

Sometimes change is forced on us, but there are also times when we want to make changes. We might want to tackle inequalities in society through our work, or creating other positive social changes. Or we might want to change some aspect of how our organisation works, maybe shifting to hybrid working or becoming more environmentally-sustainable. All of these scenarios are about creating change and these tools apply to internal and external change and are scalable from individual life changes to restructuring an organisation or creating social change.

Is it worth the effort?

Change takes effort and resource. We often need to support of others to achieve change. So, before we start making a change it’s a good idea to be really clear for ourselves and with others about the ‘why’: the case for change.

The Opportunity/Threat matrix offers a really simple format to think through the benefits of making a change, and the risks of not making it.

You basically work through 2 questions – what are the opportunities if we do this, and the risks if we don’t – in both the short-term and the longer-term. It’s up to you to define what short/long-term horizons make sense for your situation, but be specific – e.g. in the next 12 months/ the next 5 years.

It can be really helpful to involve others in this exercise. This broadens the perspectives involved in the analysis but also enables those with a stake in the decision to fully understand the arguments around opportunity and risk.

You might decide, after completing this exercise, there isn’t a strong enough case to press ahead with the change – but if there is then the following tools can help the process go more smoothly.

How to make change happen or ‘tip’?

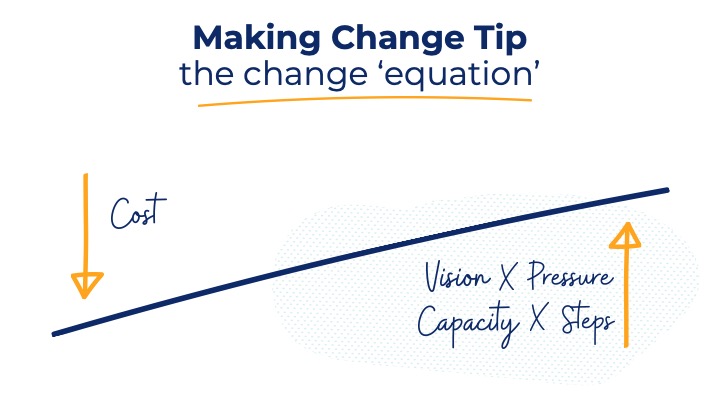

This simple ‘equation’ sums up the key considerations at play when we’re trying to make change happen. I came across this version at Henley Business School on a change leadership course and it’s based on the Gleicher modelled, popularised by Beckhard-Harris, with one important variation.

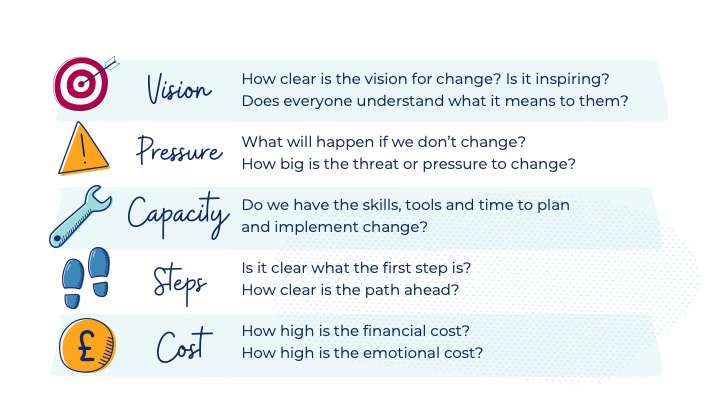

This model identifies 4 key ingredients that need to be in present for change to happen, and one factor (cost) which inhibits change. These ‘ingredients’ are outlined in the illustration below:

Change ‘tips’ when the other ingredients outweigh the cost.

This model I’ve used countless times since encountering it at Henley, includes ‘capacity’ which the original Gleicher version lacks.

In my experience capacity is often the missing ingredient in the cultural/ creative sector – we lack the time or resource to invest in enabling change. Technically this is what is referred to as ‘development capital’; resource which we can use to invest in doing things differently, experimenting, doing training, buying new hardware and software. Too often our budgets and diaries are over-committed and we lack this space and resource.

I use the equation to assess the likelihood of success of change and identify where there might be blocks so we can identify what actions are needed if change is to happen. It can be used at the planning stage, and during review of how things are going.

How to respond to unwanted change?

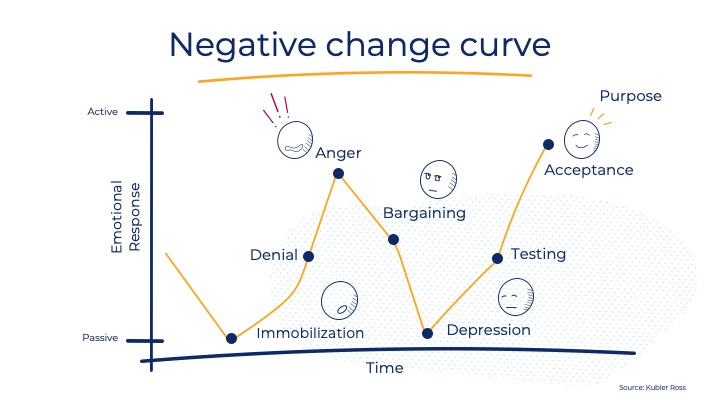

You may well have heard or seen ‘the change curve’? There are actually two curves, but the one most of us know is also known as the grief curve, as it emerged from the work of psychologist Elisabeth Kubler-Ross looking at the main stages of bereavement. However, it has also long been applied more generally to understand how we respond to external changes we perceive as negative.

I find model this helpful for a number of reasons. It can be helpful to be aware of these psychological reactions so we can be sensitive with others and self-aware. For example, it can be unrealistic to expect people to be able to quickly process ‘bad news’ and adapt, it might take some time.

And we need to be cautious not to allow ourselves – or others – to spend too much time in the ‘bargaining’ stage. Bargaining is when we offer a solution to the change which doesn’t take full account of the situation: re-arranging deckchairs on the Titanic. Thinking we’re doing ‘our bit’ for climate change by buying a re-usable coffee cup but not making the bigger changes to our lifestyles really needed.

We might need to do a little bargaining before we’re ready to accept the full reality of the situation (the ‘depression’ stage). But we want to avoid spending too much time bargaining if we want to adapt constructively to negative change and reach the stages of testing and acceptance.

The other thing I like about the Kubler-Ross change curve is that it sits well with my experience of what makes me feel better when Shit Happens (another technical term I learned on that course at Henley). Working out what I can do to be helpful or to improve things, where I do have some agency, usually helps me feel a lot better.

How to keep the momentum going?

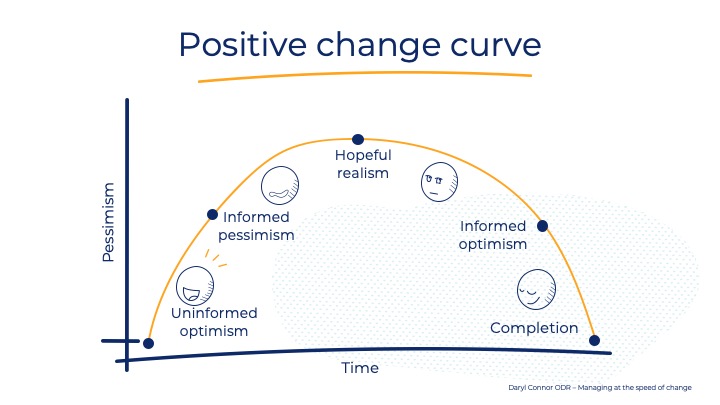

I promised you two change curves. The second applies to changes we want, hence it’s name ‘the positive change curve’. What is shows is that – basically – our enthusiasm wanes over time. We start off ill-informed about what exactly the change will involve and how long it will take, and as we discover more about the reality our optimism is likely to drop. If the gap between expectation and reality is too big we might decide to quit. But also we might form a more realistic but still positive view of the change and move into the ‘Informed Optimism’ stage.

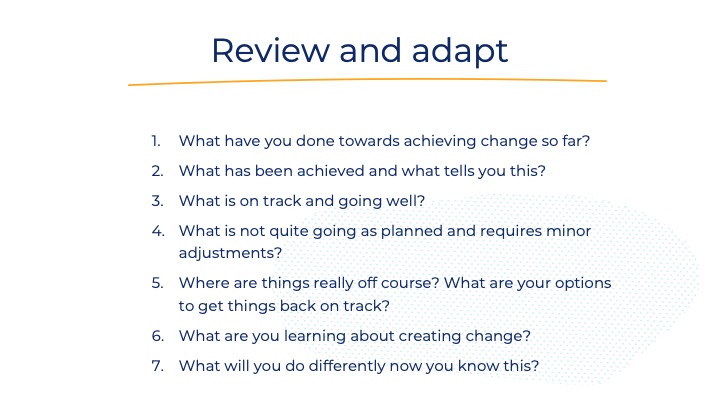

How is this model helpful? It reminds us that we need to attend to morale along the way; to celebrate our successes, give ourselves some ‘easy wins’ early on etc. Simply making time to review, constructively, and acknowledge what’s been done and achieved can be enormously helpful – and the simple set of questions are typical of the kind I use with individuals and teams to this end.

Also, the smaller the gap between expectations and reality the fewer morale issues lay ahead. So the positive change curves reminds us of the importance of realistic plans.

How to involve/ engage others?

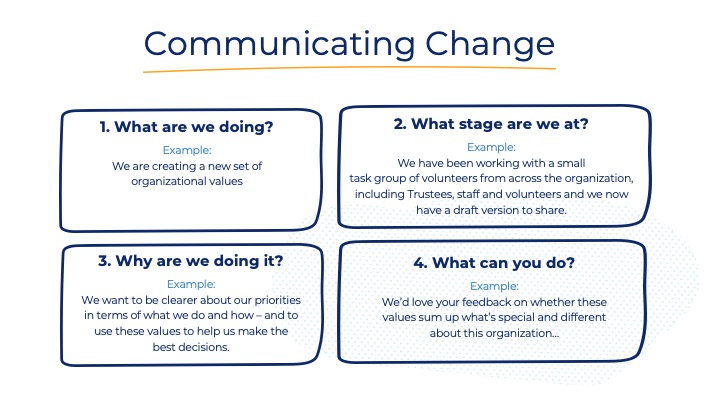

Last but not least, this final tool offers a simple framework (and worked example) of how to explain what you’re trying to do, and why, to others so you can engage them. Whether you want other people to do things differently as part of the change, to generate ideas about what needs to change or simply to support or approve of the change you’re planning – you’ll need to be able to clearly and simply explain what you’re doing, why, how and what you need from them.

These 4 simple questions are a template for those communications – whether they take place via face-to-face informal conversations, a formal presentation or written formats (or all three).

I hope there’s something in these tools that’s useful for you. If you agree with Heraclitus that ‘the only constant in life is change’, then learning a few new techniques about how to master change is time well spent.

Recent Comments