by clairesan | Mar 18, 2021 | Blog, Direction, Imagination

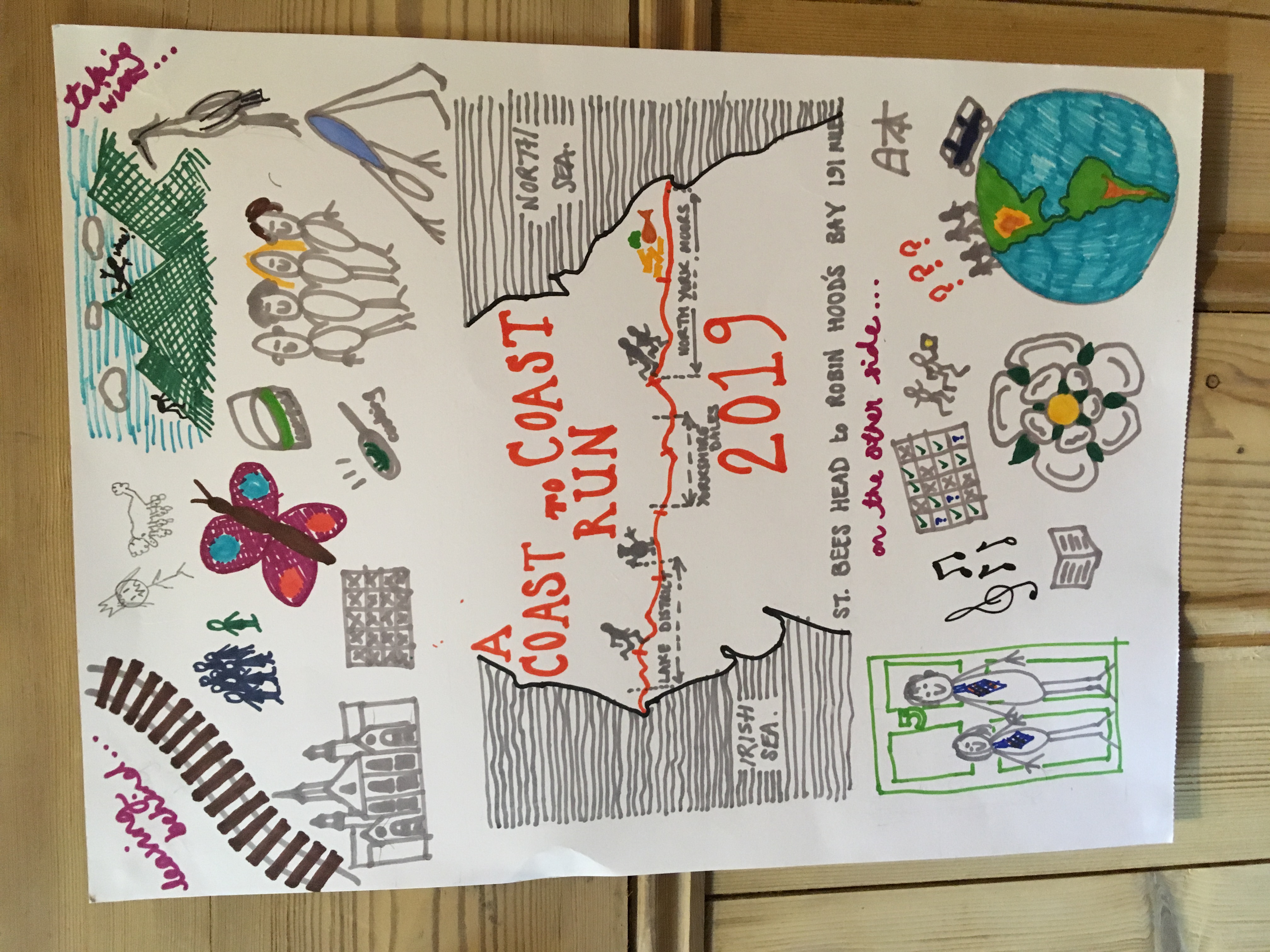

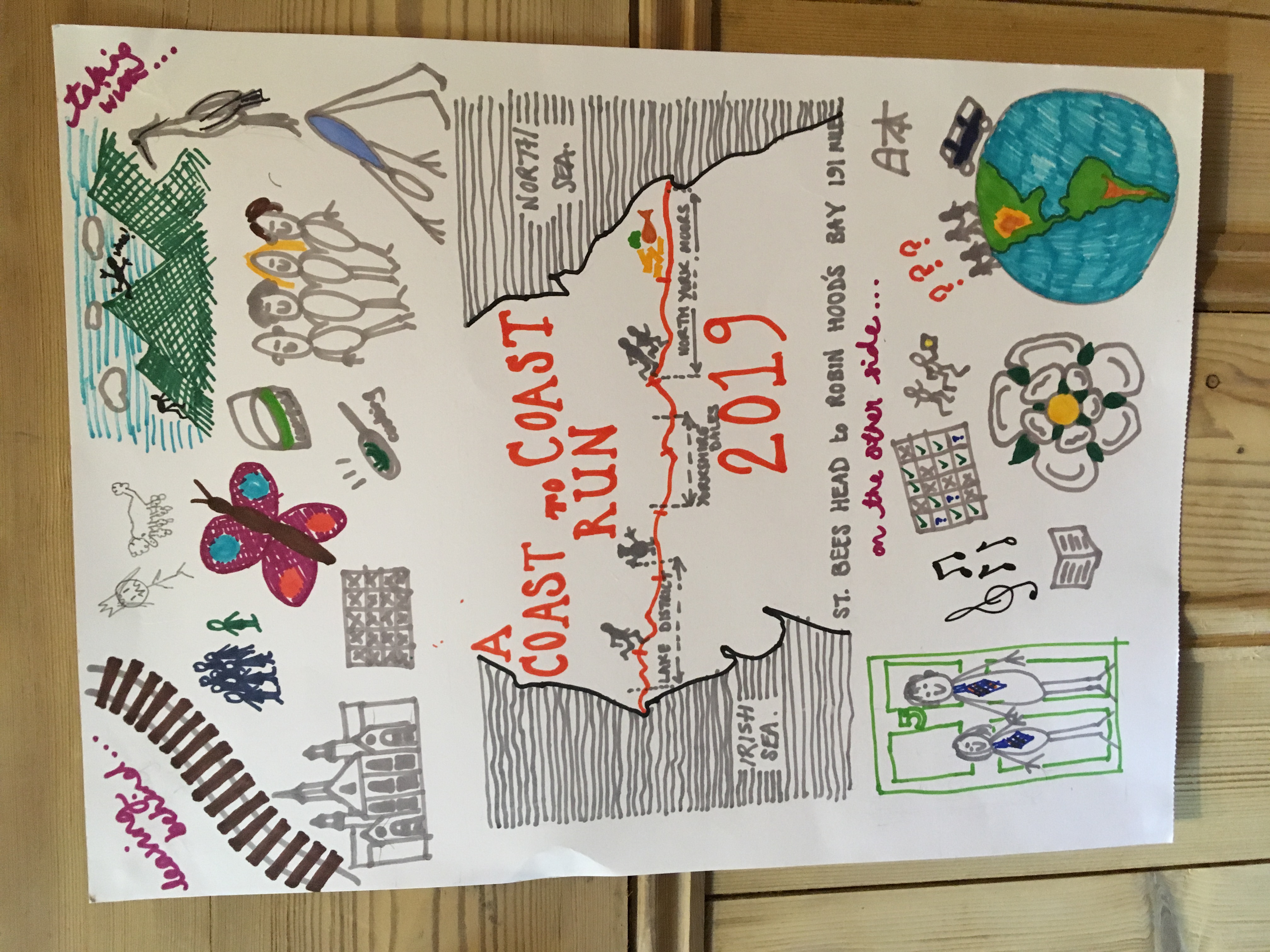

In Spring 2019 my friend Ann was visiting and as we were stuck indoors due to rain so I suggested that we sketched our dreams for the year ahead. I’m not very good a drawing, but I had done a similar exercise with my Action Learning set and found it really enjoyable so with plenty of disclaimers about ‘being rubbish at drawing’ we borrowed some felt tips from the kids’ craft drawer and spent a happy hour imagining and trying to capture our thoughts visually.

I was thinking about running the 191 mile coast-to-coast path, solo, in the September of that year. I also wanted to make some big changes in my professional life (less travel, leaving the company I was working for to go solo etc). I came up with a visual metaphor: I drew a picture with my route across the country in the middle – splitting the year into before and after, showing as best I could with images the changes I wanted to make. The lonely and challenging run visually cut the year in two and signalled also the courage I felt it would take to strike out alone.

Whilst I didn’t win any art prizes, the drawing captured for me some important decisions and I put that image on the wall of my office where I would see it, reminding myself of this commitment to make change happen.

So when, a year later, I stumbled across Willemien Brand’s Visual Thinking – a brilliant guide to using drawing in facilitation – I was delighted to have a toolkit I could use not only to enable my own thinking but with my coaching and facilitation clients.

There are two aspects to visual thinking that I am particularly excited about:

Visual thinking often involves metaphor

Metaphor can be a very powerful way to articulate change, and there is a rich tradition of using metaphor in coaching and therapy, notably David Grove’s work on Clean Language. I had been using Clean techniques in coaching for many years so the shift from talking about metaphor to drawing images made a lot of sense to me.

Some of the visual thinking tools encourage us to think in metaphors – e.g. when gathering perspectives on what enables or prevents a share goal we might use the hot air balloon image and ask – what lifts us up, and what holds us down? There is also an iceberg metaphor which encourages us to identify what’s really going on under the surface – what hazards are lurking in the depths or what hidden treasure might we find?

One of my favourite metaphors is the road map – an invitation to choose your own destination and timeline; to think about what you are taking with you in your backpack (the things you have already); and to identify the potential milestones, route choices and hazards en route.

I created myself a road map for 2020 and found it helpful to think about the ‘perils’ that might distract me from my route and encouraging to think about the things I had in my rucksack: previous experiences, tools etc. That’s a tool I shared with a few coaching and facilitation last year too – and it resonated for them too – especially at a time when more traditional ‘plans’ felt hard to write given the uncertainty.

Visual thinking helps us learn

Illustrations, diagrams and doodles can also help us remember things – sometimes we recall images or diagrams more readily than complex terms as in the old saying ‘a picture speaks a thousand words’. Dual coding theory, which suggests we learn better when as well as written language we learn a visual symbol, has been known about in education for fifty years. Put simply, our brains store verbal language and visual images separately so if for each thing we learn we ‘bank’ a phrase and an image when we want our brains to find the nugget of info there are two options to recall, rather than just one.

Byy visualising and working through aspects of a challenge or theory using drawing we can develop an understanding as well as improve recall of information and ability to apply to other contexts – as this article I saw recently in Times Educational Supplement about using drawing to learn in schools shows.

As adults, we can feel inhibited to draw because many of us don’t do it regularly these days. The Visual Thinking book addresses this head-on with tips about how to draw well for facilitation purposes. But whilst it’s handy to have a few skills and techniques, it’s also important not to worry about the finished product – it’s the process of thinking through imagery not the final image that matters. Fortunately!

by clairesan | Mar 18, 2021 | Blog, Facilitation, Review, Training

Recently I was asked to participate in a research interview for a project the British Council has commissioned around peer-learning, and the consultant sent me over some interesting questions she wants to discuss, that led me to ask my own questions about this topic…

So firstly, what is peer-peer learning?

In my experience, it can be informal, like for example the conversations I’ve had with lots of fellow facilitators of the past few months about their experience of working online, or formal, like the Action Learning set I’ve been part of for many years where we meet approx. 6 times a year for a day to learn together. Reg Revans, the founder of Action Learning, described it in terms of ‘comrades in adversity’ who come together to support one another and learn from each other’s failures and challenges, rather than from ‘experts’.

Peer-peer learning is often part of training too, whether that’s a simple as inviting explore and idea together in small groups, or practice a skill or technique in pairs during a session. Sometimes participants are ‘buddied’ during longer training programmes, and recently I was part of a learning ‘pod’; a group of 5 of us doing the same course who met for 45 mins a week to support one another’s learning.

So who’s a ‘peer’?

I think this is a really interesting question – in the (distant) past I’ve certainly been guilty of being a bit reluctant to participate in peer-peer learning as I wondered whether people had enough in common that we could learn from one another. But I’ve realised from my own experience that I’ve often learned most from people whose experience or perspective is very different to my own. Some of the most important insights I’ve had came from hearing from people with a very different experience to me – for example as a Clore Fellow, it was talking to a theatre professional, Chris Stafford, that I realised what I wanted to do/be in the visual arts sector – as the Executive Director role didn’t (yet) exist.

As a trainer who includes peer-peer learning as a tool within the courses I design and deliver, I often read in the feedback forms that participants highly value these opportunities to work with others on the course. However, as a participant I’ve also had less than brilliant experiences of this kind of learning when it’s felt that maybe the experience level in the group has been too unequal, particularly when that’s been about practising a skill or technique together or the other participants haven’t been as committed to the group.

What are the benefits of peer-peer learning?

Cost – maybe it’s because I’m a Yorkshire woman, as we’re known for being natural frugal, but one thing that appeals to me about peer-peer learning is that it’s very cheap! For the Action Learning set I’ve been part of for nearly a decade, we met (pre CV19) in one another’s homes, bringing our own ‘pot luck’ lunch so the only cost was our time, and local travel.

Relevance – peers’ experiences are likely to be similar to yours, so they can offer examples that resonate to you. If you’re asking ‘how do I…’ and the person offering advice has a much bigger budget or set of values to you, then their suggestions are less likely to be appropriate.

Safety – the founder of Action Learning, Reg Revans, described this approach to peer-peer learning as ‘comrades in adversity coming together to support one another, and learn in the process’. Peers can be supportive, and understand the challenges you face so it can be easier to share your doubts and concerns with them.

We can also embed our own learning though teaching others. A primary school teacher friend of mine explained that it is current practice to encourage pupils at different levels of skill to work together, with the ‘stronger’ pupil supporting their classmate. I asked her, wasn’t this unfair on the more able pupil? But she explained that explaining a concept to someone else helps your own learning. Whether that’s through embedding via repetition or how the brain processes information when explaining it, I’m not sure. But what she said rang true with my own experience of training coaches for several years; I would find my own understanding improved by explaining the principles, techniques and skills to others.

What kind of learning works well on a peer-peer basis?

We know from cognitive psychology that there are many different ways to learn, and we learn information or concepts differently from how we learn self-awareness or a skill. I’ve not (yet) read anything that suggests what types of learning are best-served by peer-peer models, but I have some hunches from my own experiences as a trainer and learner.

I think peer-peer learning is particularly useful in developing emotional intelligence and specifically self-awareness. A supportive peer-peer environment can be a safe space to notice and ‘un-learn’ our limiting beliefs or recognise behaviours and attitudes which might not be serving us well.

Peer-peer learning is also incredibly useful when it comes to applying concepts or techniques to real-life situations. Because peers are often able to offer their experience, this means examples are more likely to ‘fit’ our world and resonate. This is incredibly useful in training when having understood a concept, to be able to convert that learning into action there is a step of processing ‘how can I use this information’.

Most recently, as part of a learning ‘pod’ on an online course I was doing, I also experienced the benefits of accountability via peer-peer learning – we each had to read a chapter of the training book and talk about it together the next week. Not wanting to let down the others, helped motivate me to do my individual ‘homework’.

As a trainer, I’d add peer-peer learning can be useful when the participants are sceptical about the content or the learning opportunity. When ‘conscripted’ onto in-house training courses, I find participants are less resistant to learning from one another than an external ‘expert’ who has been foisted on them!

However, I wouldn’t necessarily expect to be able to learn foundation skills or concepts through peer-peer learning. To me, it feels like a follow-on from core training, rather than a replacement for it.

What makes for great peer-peer learning?

A clear agenda – even if I’m having a 60 min informal check-in with another professional, then it can be helpful to clarify what we want to get from one another and agree the best way to do it. It’s not just a chat, it’s important to have mutually agreed aims!

Structure – can be helpful. I’ve mentioned Action Learning which can be an incredibly powerful model over time, but it takes a certain degree of skill and familiarity with the process (and/or a very experienced facilitator). I often used the Troika Consulting model as a simpler peer-peer format on courses I run – as it takes less time to set up or practice and participants can easily continue to use this format after the course finishes if they enjoy it.

Equality – I don’t get hung up on titles and some variety of experience on the group is helpful, but it’s important we can see one another as peers and all learn ourselves as well as support one another. If the experience levels are too diverse then I find this can tip into more peer-mentoring than peer-peer learning, and that can impact commitment too if some people ‘gain’ more than others – especially when time is unpaid.

Diversity – different perspectives are often where biggest learning happens, so opportunities to learn from other sectors, other countries, people with a very different ‘style’ to me – all of these are valuable – so long as we have shared interests or values (there has to be some commonality).

Ground rules – confidentiality is often important, to be able to share openly, especially those things that are not going well. I value being able to be really open with my peers and I’m willing to share information widely, if we’re clear about the boundaries. Personally I like to ‘contract’ that we balance support with challenge – it’s a learning space, not a support group!

So, I’m a big fan of peer-peer learning and intend to keep doing it, formally and informally, and including it as part of my work as an Action Learning facilitator and trainer. Peer-peer learning isn’t a panacea though: I see it as one type of learning, but not the only one I deploy as a trainer or seek as a learner. It’s suited to some types and stages of learning, and requires a bit of support or structure to be effective.

I would love to hear other experiences and views on these question though – as well as find out more about research in these areas… so get in touch!

by clairesan | Mar 18, 2021 | Blog, Coaching, Consultancy, Direction, Navigation

Setting goals is a key part of coaching – imagining and articulating the destination, where we want to get to, is an essential stage in making change happen. In fact, in the popular GROW model of coaching, setting the goal is the first step – the G of GROW. We decide on the destination (Goal), before we take stock of where we are now (Reality), develop ideas and possibilities about the route from A to B (Options) before finally deciding on our course and making a detailed plan (Will).

Why goals are helpful?

There’s lots of research as to why goals are helpful in creating change:

- They can be motivating – knowing where you’re heading, having imagined and articulated success generate a sense of purpose; a key ingredient in motivation. Also having clear measures of success means we are clear when we’ve achieved a goal, and have a sense of satisfaction.

- Having a clear sense of where you want to be, especially if it’s exciting and a bit ‘stretching’, is proven to improve performance (see Locke’s Theory).

- If you’re part of a team, having common goals means you’re all pulling in the same direction – like a train – as opposed to heading off in different directions – like a octopus.

How to create useful and motivating goals?

There’s an art to creating useful goals – the ExACT framework is one I typically use in coaching – ensuring a goal is measurable, challenging, time-based. It’s similar to the SMART objectives model that’s widely used in workplaces, but with a few important shifts of emphasis. Using a framework like ExACT helps us avoid the common mistakes of creating negative or nebulous goals – and ensures we personally find it exciting, and therefore motivating.

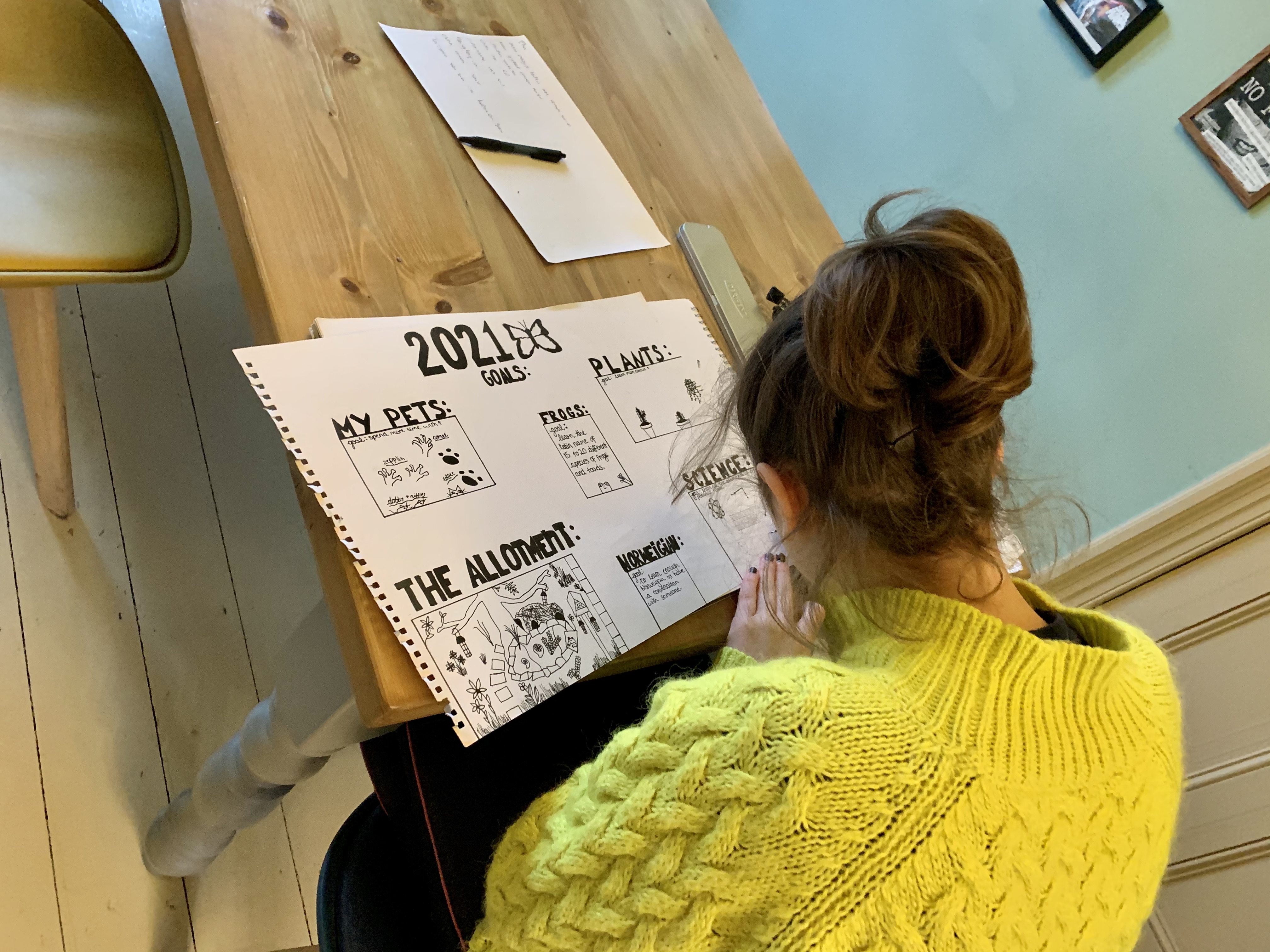

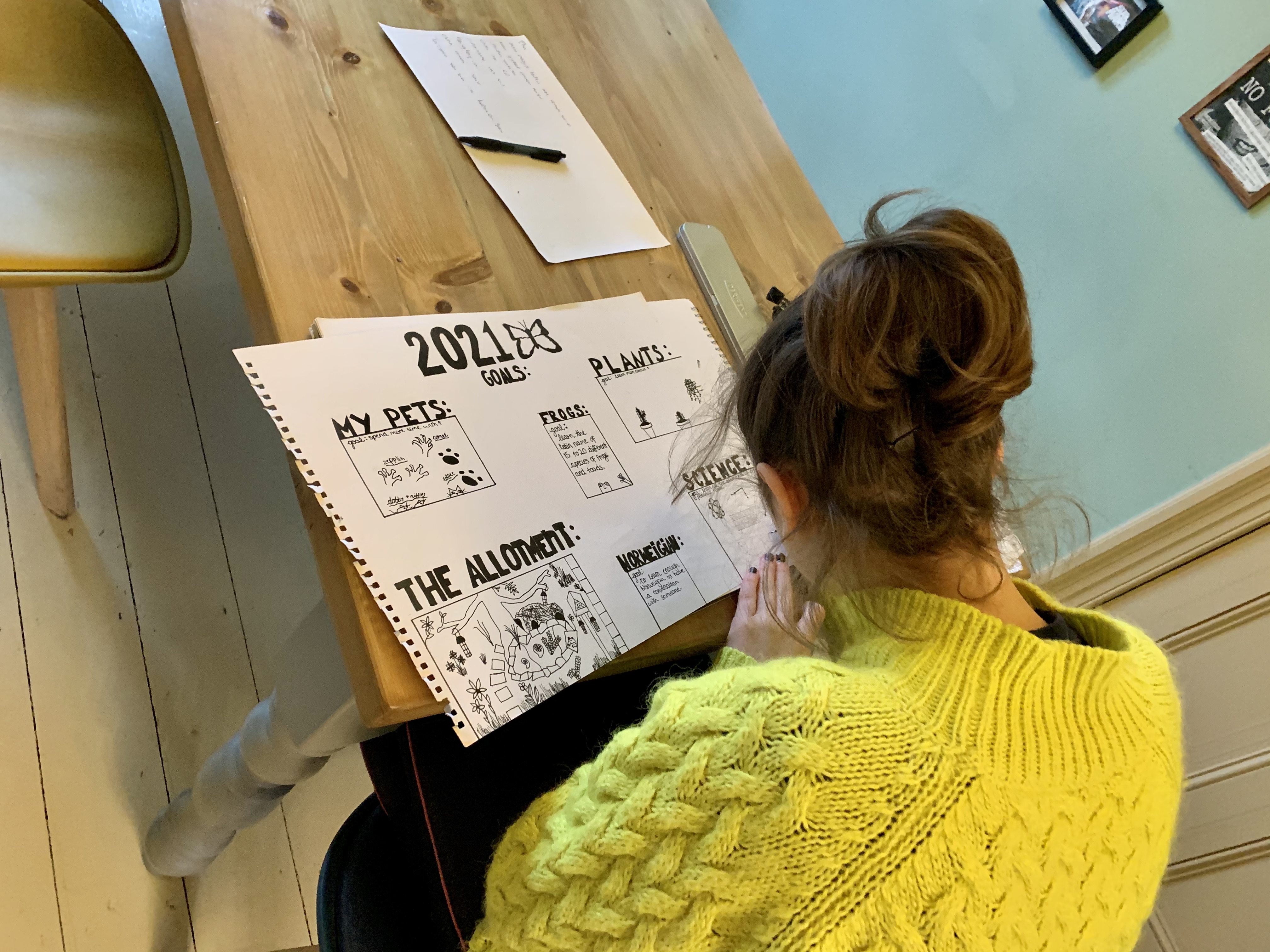

Goals can be written down, or sketched – but they need to be short and memorable. I like to capture mine simply – either as a table of 3-5 goals or a sketch. Currently I’ve sketched my annual goals for 2021 and have a simple table of my 3 month goals at any time – both are stuck on my office wall where I can easily see them. ‘Explicit’ means we’re more likely to have them ‘in mind’ when making decisions and therefore they are more likely to happen.

Avoid focussing on the wrong things

Equally important is to choose a goal that’s within your control – we can’t control whether we ‘secure £50K from Trusts and Foundations before end March’, but we could set a goal around ‘submitting high quality grant applications to Trusts and Foundations totalling £50K before end March’ (NB. as a former fundraiser I’d advise applying for significantly more finds than you want to secure, but that’s a bit beside the point).

And just as important when setting a goal is to focus on the outcome not the process – otherwise we risk chasing after the wrong thing. Fans of The Wire will recall what happens when the Baltimore Police leadership focus solely on numbers of arrests; it skews policework and how crime is reported, but does nothing to improve levels of crime on the streets. We need to measure what matters: the goal is probably about job satisfaction or work/life balance not ‘getting a new job’.

And, whilst ‘nailing down’ some good clear goals is always a useful process, it’s important not to get to wedded to them; goals can change as we move towards them, it’s often an iterative process.

But don’t get too hung up up goals – keep things fuzzy or revisit and revise goals if that helps you

I recently came across the concept of ‘fuzzy goals’; the notion that a sense of direction rather than a precise destination can be a useful way to proceed when the way ahead is unchartered. Having a general direction of travel, but being open to opportunities along the way, resonated with how I like to walk in the hills – I have a plan when I set off but I’ll adjust it according to the weather, my energy levels, whether I spot a nice detour, the pace we’re travelling at etc. So starting with a destination in mind, but keeping checking that’s still where you want to head given what you’re discovering en route, is another way to set goals.

The Road Map exercise can be a good place to start planning your goals, and those key milestones along the way.

Of course, goals don’t just happen – we need ideas, plans, reviews and effort – but goals are a great place to start if we want to move forward.

by clairesan | Mar 15, 2021 | Blog, Direction, Momentum

Want to do or change something but know you’re going to find it a struggle? Maybe you;ve tried before and not managed it? Find yourself setting goals or committing to new habits which you find it hard to stick to? Then accountability could be your friend….

When we commit ourselves to achieving something specific and measurable we are more likely to achieve it. Research shows that simply the act of writing it down, or saying it aloud, or rather than thinking it to ourselves means we are more likely to do it. That’s why on training courses you are often encouraged to share publicly the actions you plan to take – as trainers know that’s more likely to embed your learning by leading to practice.

As with any goal, to work well accountability requires clarity – if we say ‘I want to get fitter’ we are less likely to succeed than if we commit to ‘I want to walk 3 miles every day’. And, again as per goal-setting generally, we are more likely to put in the effort required if we own the goal as opposed to if someone else has told us to do it.

I’ve sometimes noticed, as a consultant, a reluctance to clarify measure of success – perhaps because the client fears failure and so being a bit fuzzy about the outcomes allows this question of success to be fudged. It’s true, some things are harder to measure than others, but we can usually make a reasonable assessment ifwe want to.

So accountability can be really simple to achieve – writing it down our goal and sticking it somewhere we’ll see it often can be enough to create the focus we need and encourage action.

Struggling with something and need to take accountability up a notch? Then bring in a social aspect to accountability – tell other people what you intend to do. If you’ve posted on social media that you’re going to run 13 miles that day when it starts rainin and the voice in your head suggests after 6 miles that you could just stop, then the prospect of telling others you didn’t stick to your word can help you keep going.

If you’ve committed yourself publicly to doing something that sense of shame if we have to admit we’ve failed can create another level of accountability. Just as knowing the support and recognition you’re likely to receive can help motivate. It’s like using the carrot and stick technique on yourself.

I was reminded of the power of social accountability when I accepted to sign a Twitter pledge recently not to fly in 2021. I had already decided (pre CV19) not to fly in 2020 and had planned holidays in locations we could reach by car or train, but I was wavering about a race in the Dolomites I have entered for June 2021. Getting there without flights would be very difficult without a lot of additional cost and travel time (days, not hours, extra). But once I’d signed this pledge (and publicly shared in on Twitter, where random strangers had ‘liked’ my pledge) I felt more accountable for this commitment already.

Arguably this technique isn’t too healthy or effective to rely on long-term but it can offer a boost when things are tough and you need that little extra push to keep going. For example, we know that when you start running if you arrange to go for a run with another person you are less likely to change your mind and skip that day. However once you’ve developed a habit of running and begin to enjoy it (honestly, that does happen) then you don’t need the social accountability of a running buddy to get out of the door each day.

As a coach I offer accountability to coachees – encouraging them to set themselves clear targets, specific actions to follow up between sessions, and checking in to see how they are progressing. I’m careful as a coach not to judge ‘success’ in following up goals or actions – that’s for the coachee to determine, they might not have completed an action because they had other priorities or their goals might evolve over time.

But accountability – in the traditional sense of holding oneself to account does have its uses. Above all else, it helps us keep ourselves honest about what really matters to us and whether we do what we say we want to.

by clairesan | Mar 13, 2021 | Blog, Direction

You don’t need me to tell you that it’s been a strange 12 months. But for me it’s also been a period of positive change. As the anniversary of the National LockDown on March 23rd approaches I find myself ready to turn a new page and launch my new website and newsletter, informed by what I learned during these strangest of 365 days.

Whilst I was fortunate compared with many my work and life were still disrupted. Suddenly all the training and facilitation work I’d spent years building up was cancelled overnight, and many clients disappeared onto furlough. There were many times when I worried about friends and family, money, what my children were missing out on whether was I was doing was helpful enough. My confidence really plummeted at one point too.

I threw away the 2020 diary in which I had plotted my plans for the year rather than have to see them scribbled out and be reminded. I took several months off work to look after family in April-June, but during the autumn I took the rare opportunity of a bit of space in my diary to re-think and re-build. This what I discovered:

It takes a pandemic to finally sort out my work-life balance….

I had been trying to reduce work travel for several years, but CV19 forced this change and overnight I went from spending on average 4-5 nights away from home each month and many hours on trains to working from home every day. On a personal level plans to fly for holidays were shelved, and I’ve pledged to stay Flight Free for 2021. I love travel, but I want to reduce work travel significantly even when it’s possible again.

It’s been a year for coaching…

Since training as a coach in 2010 I have used coaching in all areas of my work, every day, as a change consultant, manager, facilitator. But being based in York meant that I was able to work with fewer coachees than I would have liked. Online working has completely changed who I can work with and this year I’ve worked with clients from across the UK – and I have loved being able to spend more of my time coaching.

I have realigned my business model with my values …

I also started to offer Pay What You Can coaching to enable those people experiencing hardship to access support. This meant trusting those who could afford to pay would do so, and being transparent about how I set my ‘guide’ hourly rate to enable people to make informed decisions.

Like many other people I wanted to be more useful in the world but I couldn’t find a way to do this via my work. I considered retraining (not in ‘cyber’) although the options generated by that government careers algorithm didn’t feel right either: boxer, soldier, bingo caller. Seriously though, I considered radical changes in what I do for a living but decided in the end to stick with what I do and instead donate funds to those better placed to make a social impact: Bloody Good Period, Slung Low and You Make It. I decided to cap my earnings at national average and any ‘profit’ I now make above my target income goes to those causes.

Capping my earnings also has benefits for me – it has helped me stop over-working. As a freelancer income can be variable so it can feel hard to say ‘no’ in case a rainy day is around the corner. That has meant there have been many times I have worked too hard and become exhausted. I’m trying to stop hoarding and instead to trust there will be enough work. Another benefit of this is that I now have more time…

I have had space to experiment and learn…

I love discovering new tools, ideas and theories, but in the past it has been hard to find time to research and experiment. 2020 gave me space to read some books, do the courses, and process the learning I’ve wanted to do for YEARS. And it was wonderful! I swear I can almost feel my brain has grown this year.

I’ve also rediscovered my love of drawing and how useful illustration can be for facilitation, learning and coaching thanks to concepts like Visual Thinking. I’ve embraced using metaphors to explore ideas, and visual tools to embed learning.

This period of R&D brings us up to date – to March 2021 – and my appetite to share some of these tools and techniques via my new website and monthly newsletter. I’d love it if you were interested in signing-up to receive the newsletter.

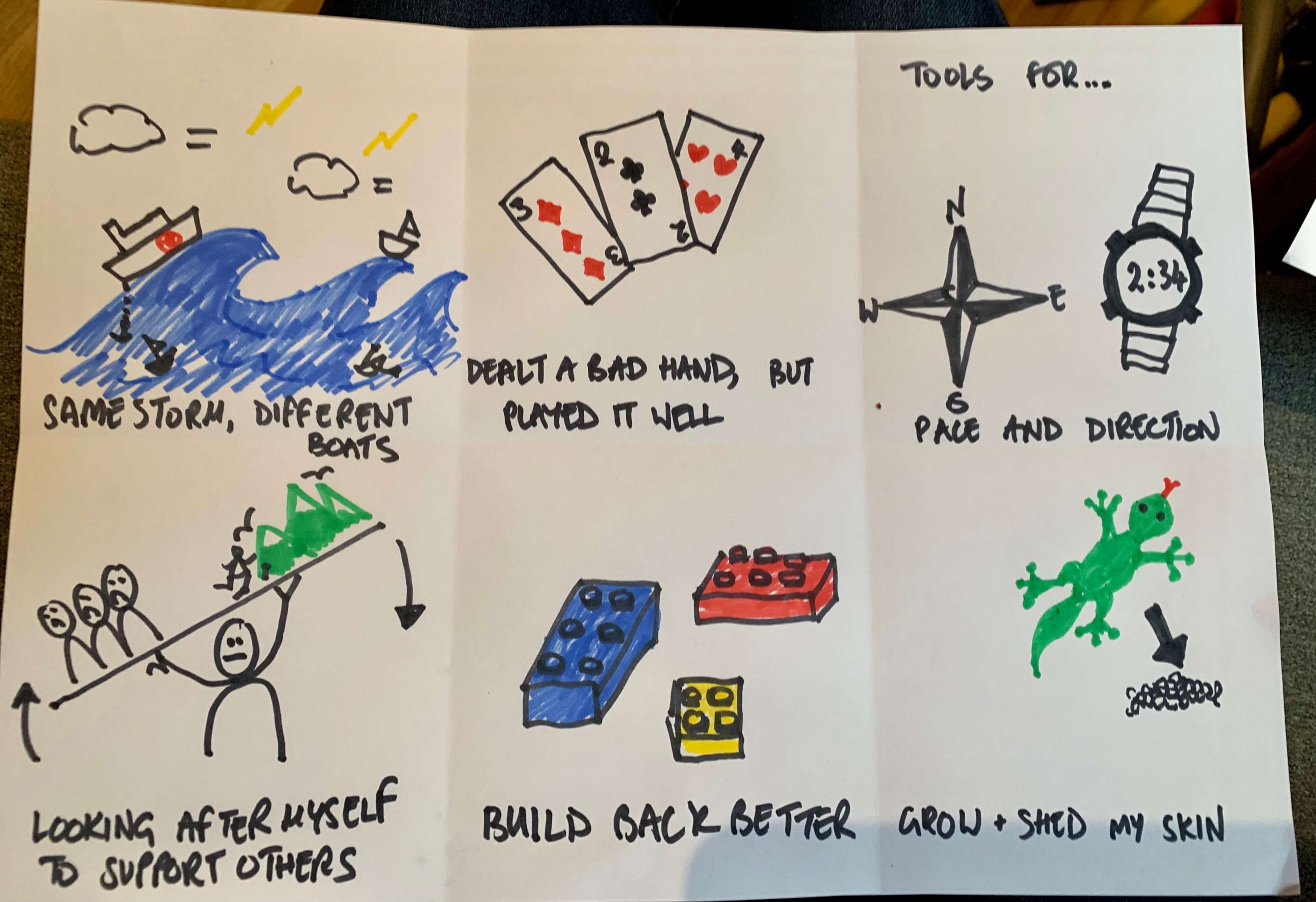

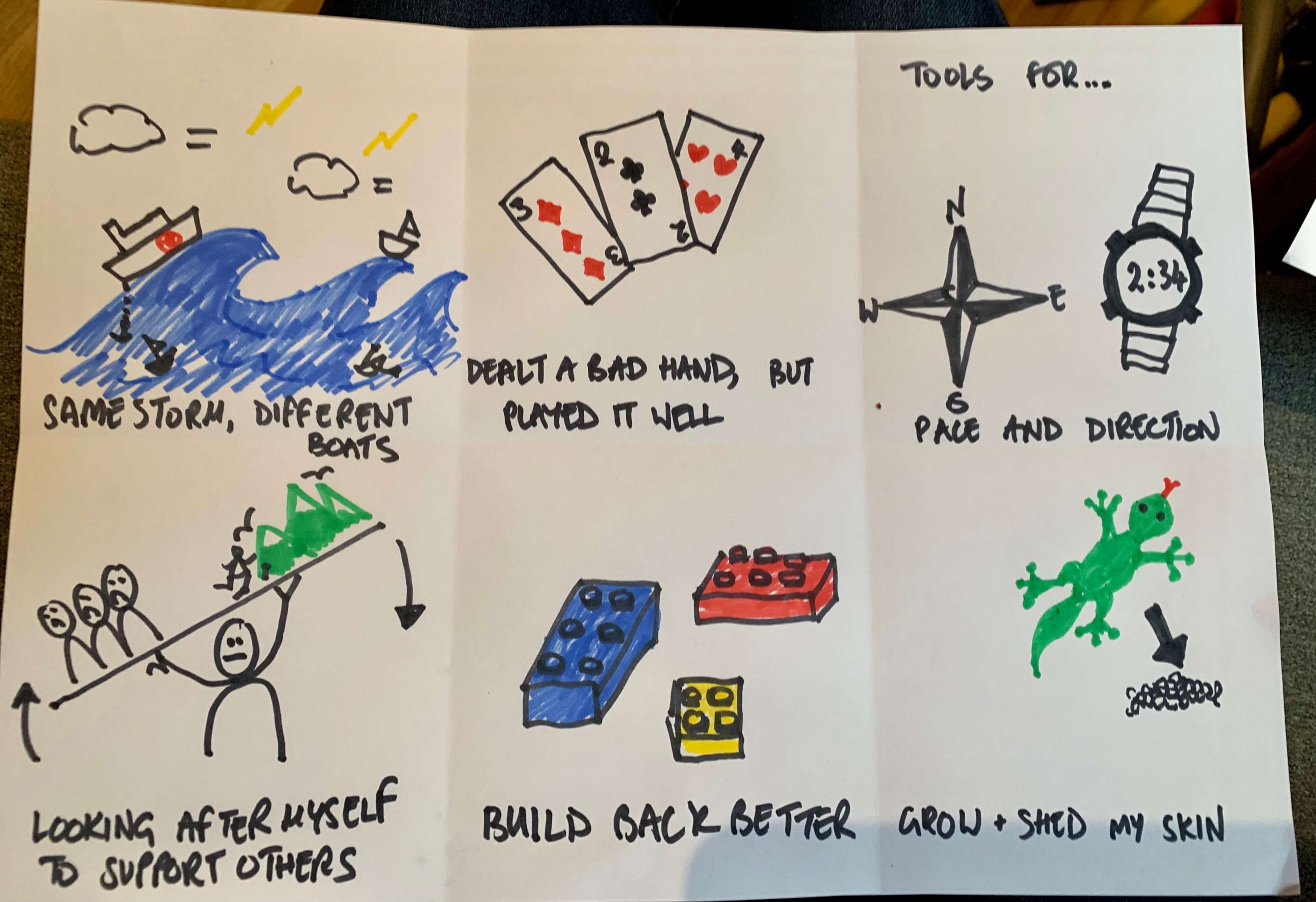

This past year has been hard, but it has also been good to me and I feel grateful as it’s been an absolute shocker for many. In May 2020 I was asked to contribute to an ‘expert panel’ about how arts organisations might respond to the crisis. Not sure what advice I could usefully offer I simply challenged the saying I was hearing a lot at the time ‘we’re all in the same boat’ because quite frankly if there was one thing 2020 did well was it threw into stark relief how unequal our world is. I said we might all be in the same storm but our boats are very different – some people have large yachts, others have tiny rowing boats without oars.

Maybe it’s because this year has been so exceptional that I’ve found myself turning to metaphor more and more, but it’s another form of visual thinking. And right now there’s another metaphor forming as I review the year just gone – I didn’t like the cards I was dealt, but I’ve played them as well as I could.

by clairesan | Feb 28, 2021 | Navigation, Resource, Tool

An exercise designed to enable you to reflect on what motivates and matters to you, based on previous roles.

Recent Comments